|

|

|

|||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

Humayun Azad: Some

words of bereavement from Mukto-mona’s Advisory Board

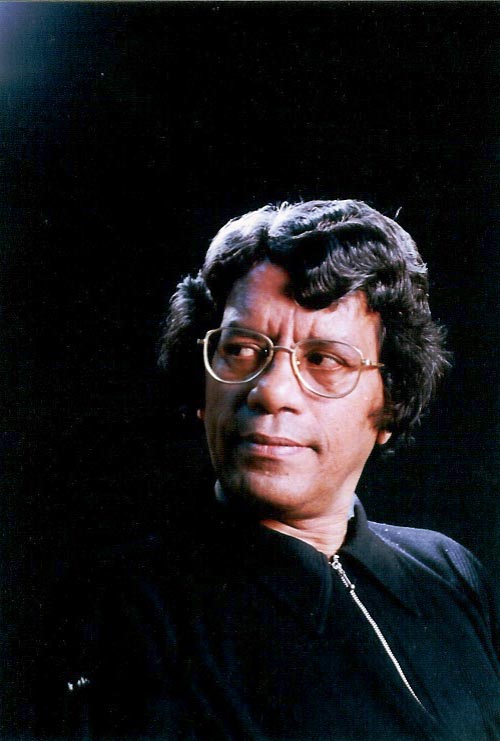

Professor Humayun Azad, a distinguished member of Mukto-mona, had passed away on August 11, 2004, in Munich, Germany leaving us to grieve his death. The professor was one of a rare breed in Bangladesh where freethinking and rationalism have taken a backseat. Thanks to religious fervor and growth of extremism that has overshadowed whatever little freethinking was in the offing. Professor Azad was a beacon of both hope and light in this dreadful time in a nation. That being extinguished, whatever little hope we saw in the horizon will it now wither away? But we have to be an eternal optimist or else, life won’t move forward. Therefore, we hope that his mettle will be passed onto new generation.

This is however a time for us to bereave Professor Azad’s demise alongside with his family members and his friends. Professor Azad’s relentless fight against bigotry, religious fanaticism, and communalism, will continue. Mukto-monas (freethinkers) fought alongside with Professor Humayun Azad to fight against the proverbial cancer ushered in by obscurantism, fundamentalism, and all the negative forces of our society as the nation takes a retrogressive journey. Nonetheless, our passionate fight against them will continue. We shall overcome the obstacle. Professor Humayun Azad even though has departed us as we fight the evil force but his spirit will live forever amongst us. Biographical details of Dr Azad Dr. Humayun Azad was born on 28 April

1947, in a village named Rari Khal, in Bikrampur,

now in the district of Munshiganj,

Bangladesh. He had his secondary

education finished at Sir J C Bose Institution of Rari Khal, where he was known

as a shinning student with acumen. He

passed his Matriculation examination in 1962 with a place in the merit list of

the East Pakistan Secondary Education Board. He was a student of science

during Higher Secondary level (HSC) and after passing HSC, he got

himself admitted to the Department of Bangla at Dhaka University where

he stood first class first in both BA (Honors) and MA exams in 1967 and

1968, respectively. He had

received his PhD in Linguistics during 1976 from the University of Edinburgh,

England. His dissertation title was: “Pronominalization

in Bengali using a transformational generative framework”.

He was considered the greatest living Bengali linguist. Dr Azad was married to Latifa Khanam and

has left behind three children: two daughters and a son, namely, Mauli Azad (an advocate), Smita

Azad (a student of BBA), and Ananya Azad (a student of class X). He lived with his family at 14E Dhaka

University Residential Area, Dhaka. A summary of his work as a teacher and a writer with a few references: Dr Azad was a versatile, prolific, and non-conformist writer in Bangladesh. He was simultaneously a poet, a novelist, a critic, a linguist, a political analyst, an essayist, and also an author of quite a few books for children. Two of his books have been translated and published in Japanese language. He was an outspoken feminist as well and had written the only definitive book on woman in Bengali literature named Nari (the Women); which was banned in 1985 by the then military regime. Dr. Azad, however, went to the High Court of the country, and won the case in 2001. So far, he had published about 70 books; a short list of which is given below:Poetry1973 Alaukik Istimar (The Unearthly Steamer) 1980 Jvalo Chitabagh (The Panther, Burn) 1985 Shab Kichu Nastader Adhikare Yabe (Everything will go to the Possession of the Worst) 1986 Yatoi Gabhire Yai Madhu Yatoi Opare Yai Nil (Honey as I go Deeper It is Blue as I go Upper) 1990 Ami Benchechilam Anyader Shamaye (I Lived in Other People’s Time) 1993 Shreshtha Kabita (The Best Poems) 1998 Kaphane Mora Asrubindu (Tears Wrapped in a Shroud) 1998 Kabyashangraha (Collected Poems) 2004 Peronor Kichu Nei (There is Nothing More to Cross) Novels and Short Stories1994 Chappanno Hajar Bargamail (Fifty Six Thousand Square Miles) 1995 Shab Kichu Bhenge Pare (Things Fall Apart) 1996 Manush Hishebe Amar Aparadhsamuha (My Sins as a Man) 1997 Yadukarer Mritya (Death of the Magician) 1998 Shubhabrata, Tar Shamparkita Shushamachar (Shubhabrata, and His Gospel) 1999 Rajnitibidgan (The Politicians) 2000 Nijer Shange Nijer Jibaner Madhu (The Honey One’s Own life with Himself) 2001 Phali Phali Kare Kata Chand (The Moon Sliced into Pieces) 2001 Upanyashshangraha V0l 1 (Collected Novels Vol 1) 2002 Shrabaner Brishtite Raktajaba (China Roses in the Shraban Rain) 2002 Upanyashshangraha V0l 2 (Collected Novels Vol 2) 2003 10,000, ebang Aro 1ti Dharshan (10,00, and 1 More Rapes) 2004 Pak Sar Jamin Sad Bad (The Sacred Blessed Land) 2004 Ekti Khuner Svapna (Dreaming of a Murder) Research and Critical Works1973 Rabindraprabandha/Rastra O Shamajchinta (Socio-Political Thought in Rabindranath’s Essays) 1983 Shamsur Rahman/ Nisshanga Sherpa (Shamsur Rahman, the Lonely Mountain Climber) 1987 Shilpakalar Bimanabikikaran O Anyanya Prabandha (Dehumanization of Art and Other Essays) 1990 Bhasha-Andolan : Shahityik Patabhumi ( The Literary Background of the Language Movement) 1992 Nari (Woman: This book was banned by the government, and later freed by the Highcourt) 1992 Pratikryashilatar Dirgha Chayar Niche (Under the Long Shadow of Reactionary Thought) 1992 Nibir Nilima (The Azure Sky) 1992 Matal Tarani (The Drunken Boat) 1992 Narake Ananta Ritu (Innumerable Seasons in Hell) 1992 Jalpairanger Andhakar (Olive-colored Darkness) 1993 Shimabaddhatar Shutra (Rules of Limitations) 1993 Adhhar O Adheya (Form and Content) 1997 Amar Abishvash (My Unbelief) 1999 Nirbachita Prabandha (Selected Essays) 2001 Dvitiya Linga (A Translation of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex) 2003 Amra Ki Ei Bangladesh Cheyechilam (Did We Want This Bangladesh) 2004 Dharmanubhutir Upakatha o Anyanya (Myth of Religious Sentiment and Others) Works on Linguistics1983 Pronominalization in Bengali 1983 Bangla Bhashar Shatrumitra (Friends and Foes of the Bangla Language) 1984 Bakyatattva (Syntax) 1984 Bangla Bhasha (Vol 1) (The Bangla Language) 1985 Bangla Bhasha (Vol 2) (The Bangla Language) 1988 Tulanamulak O Aitihashik Bhashabignan (Comparative and Historical Linguistics) 1999 Arthabignan (Semantics) Juvenile Literature1985 Phuler Gandhe Ghum Ase Na (The Scent of the Flowers does not let Me Sleep) 1989 Abbuke Mane Pare (I Remember My Father) The Islamists had been against him for the last twenty years for his views on religion. His books Amar Abishwas (My Unbelief), and recently published novel Pak Sar Jamin Sad Bad (The Blessed Sacred Land) that depicted the atrocities of the Islamist fundaments in Bangladesh angered them profusely and they decided to offer a fatwa to kill him on the charge of apostasy. They attempted to kill him on February 27, 2004, but Dr Azad had survived the deadly attack after remaining in coma for four days. Fundamentalist were all along active, they wanted to kill him and eliminate his family too. Dr. Azad revealed his anxiety in his open letter to the Prime Minister, leader of the main opposition, and compatriots. Professor

Azad was a beacon of both hope and light in the dreadful time for a nation

that is probably undergoing the worst period since the history of its birth in

1971. Crucial question now is: with that ray of light being extinguished,

whatever little hope we saw in the horizon; will it now wither away? Our

answer is a straight ‘No!’ for a pessimistic tone would NOT be the right

tribute to this brave hero. Readers could recall- fearing loss of his life,

recently, we, on behalf of Mukto-Mona, contacted Dr. Azad and asked- if he

needed any kind of asylum for himself and his family outside Bangladesh. “No!

I am not an escapist! I cannot yield to mediocre mullah’s pressure. I will

not leave my country to their advantage.” Such was his courage!

Such was his determination. While on one hand, he was having a tough time

dealing with sick and mad gang of mullahs; nevertheless, on the other hand, he

fearlessly continued criticizing mullahs with such candid statements as

“with Saudi Arab’s money Jamayat is conducting terror across the

country”, “Mosques, the holy places of worships, are being converted into

an industry of producing religious fanatics.” Dr Azad was a popular teacher from the very beginning, and his students consider him the best teacher they ever had. Dr Azad was a fluent speaker; he spoke his own inimitable Bangla, which made him immensely popular. There was almost an uprise of students and the public in Bangladesh in the aftermath of his attack by the Islamist on February 27, 2004. Mukto-Mona had several mail exchanges with Dr. Azad in recent times and the above information was composed based on those exchanges. Sunday, July 26, 2009

|

|

||

|

|

|

|||