|

|

|

|||

|

|

||||

|

|

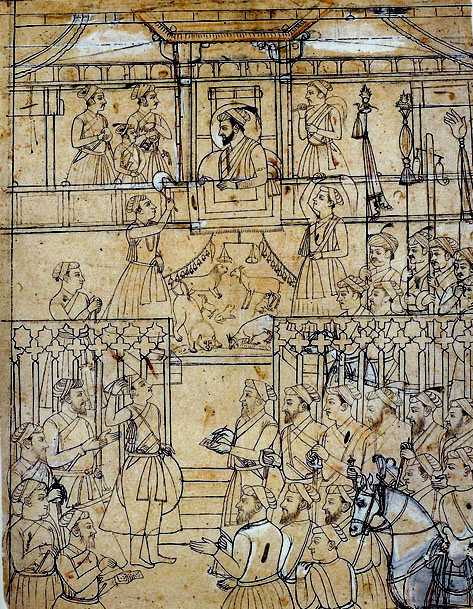

Cosmic Animals; or, the Allegory of the Peaceable Kingdom, examples drawn from a Shah Jahan Darbar Portrait (18th c.) and a 20th c. Pakistani Popular Poster* This paper compares a pictorial figureĖa visual animal allegoryĖoften placed in portraits of the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, (as well as in some earlier emperorsí portraits), with a similar figure found in a Pakistani printed poster dating from 1979. Renowned Mughal art scholar Ebba Koch labels this figure the "cosmic animals," consisting of a scene where natural enemy animals are assembled peaceably together under the aegis either of a deity, or a divine-like king. This allegorical figure entered India during Akbar's reign, when it was introduced as an illustration in a Bible brought to his court by Jesuits from the west. In that document it signified the peaceable kingdom under the rule of the Messiah to come (Koch:2001). Mughal artists picked up the figure and incorporated it in emperor portraits, like the one illustrated here:

Versions of this animal allegory of the peaceable kingdom are found repeatedly in Shah Jahani imperial portraits. This image, belonging to the Kotah raja's art collection, is post-Shah Jahan. The emperor's head is encircled by the halo of divine election or endorsement. The animal allegory can be seen in the very center of the drawing, located under the emperor's jharoka and between the whisk bearers. For clearer focus on the animals, I add a detail from this picture here:

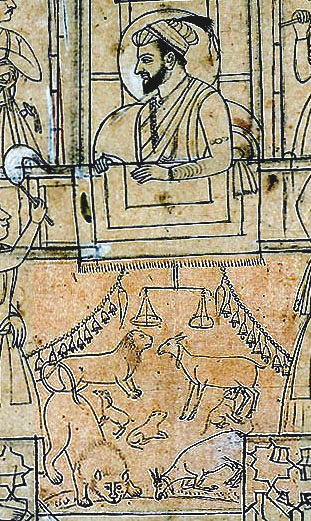

Here Shah Jahanís cosmically endorsed presence naturalizes the myth of his divine power to bring about peace in the kingdom. To elaborate on the animal action: We see a male lion and a female goat, natural enemies, drinking from the same pond at the base of the inserted figure. Above, on the right, a female goat nurses a baby lion; on the left, a baby goat looks eagerly up at another lionís belly but the lion is a male, judging by its mane, a humorous touch of the artist, perhaps. The lion, being a kingly symbol, would not be presented as giving its milk to a mere goat. The scene is completed by including the weighing scales of justice above the animals and just below the emperor's window, together with the chain of bells that petitioners could shake to call themselves to his august attention.

The emperorís portraits were meant directly to glorify him and his judicial agency in the world rather than to reflect a specific legal code (for example, like sharia). There is no inscription. The medium of the animal allegory tells the desired story for the benefit of subjects who may see the picture.

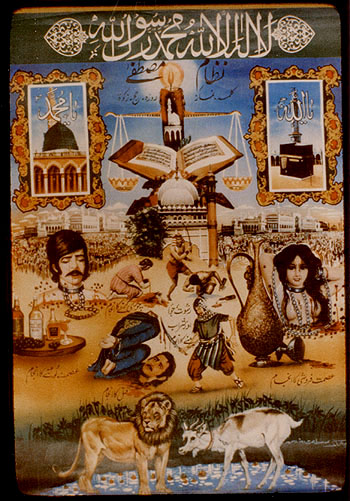

Now let us turn to a 20th century Pakistani poster (1979).

Again we see the cosmic animals, lion and goat, this time standing together in the pond rather than drinking together from it. The scales of justice are above them. But instead of a divinised king or a deity presiding above the allegory, here the scales of justice surmount the Holy Quran. The deity, Allah, is implied but cannot be figurally depicted. There are people in this picture, but they are human beings explicitly representing misdeeds and punishments. While conservative tradition has tended to avoid putting human and animal figures in depictions of the Quran, here they are blatantly present.

The possible genesis of this poster might run as follows. In 1978 Pakistanís premier, Gen. Zia-ul-Haq, announced that Pakistani law would be based on Nizam-e-Mustafa (law of the Prophet) as institutionalised in the sharia, the Muslim code of law. This poster dates from the year following after Gen. Zia decreed the establishment of Shariat courts. A year later, Islamic punishments were officially stated in public prints (newspapers and the like) listing such violations as drinking alcoholic beverages, murder, theft, prostitution, rape, adultery, and bearing false witness. Most of these sins are inscribed in Urdu on this poster. The inscriptions do not directly quote from the Quran, but they state the punishments for specific sins, drawing on the sharia that is sourced in the Quran as well as in Hadith and other texts. The inscriptions on the poster are in Urdu instead of Arabic, as Urdu is the official language of Pakistan which every literate person presumably can readĖas opposed to Arabic, which few persons other than clerics could actually comprehend. This rendering thus hints at the power of the spoken word. This is, after all, a poster meant to be publicly disseminated. The _expression of these misdeeds rendered in Urdu must evoke audio-memories in the minds of poster viewers of the admonitions given by parents, and by teachers in madressahs. Thus, the poster presumably would be more effective using Urdu rather than Arabic for its message.

Now to elaborate on the implied narratives in the poster: Let us first consider the larger human figures displayed in the middle of the poster, half of a man and half of a woman. Why halves? because they are obviously buried and being stoned (note the tiny black dots on and around them.) To the left just under the buried man is a tray holding whiskey bottles, a cocktail glass, and a bunch of grapes. Just below the naked buried woman to the right is a large pitcher next to an overturned wine cup, with visibly spilled liquor spreading on the ground. Both of them are wearing neck shackles. These sinners are depicted as undergoing capital punishment according to sharia law. Blood issues from the woman's arm and one breast. The manís eyes are closed as if he is already dead. Under her image an Urdu inscription says, "punishment for prostitution." Below the man whipping a sinner it says, "punishment for bribery, theft, gambling, and drinking alcohol." To the left of this image is a man with chopped off hands, near which is written "punishment for theft." Under the decapitated man it says, "punishment for murder." Under the plate of wine bottles below the male buried figure the inscription is not clear and my translator could not make it out, but one conference viewer thought that it said "punishment for rape."

Centered above these sins and punishments in the higher register of the picture is a mosque dome supporting an open book, the Quran. The right and left "window images" of Mecca and Medina are common to many versions of the South Asian Muslim poster. Above the mosque is a tiny minaret inside a lighted candle, shown as the fulcrum of the scales of divine justice. The burning candle signifies the nur ul Islam (light of Islam). Next to the candle are listed the five religious obligations incumbent on all faithful. Above the scales is written in Urdu, Nizam-e-Mustafa, the law of the Prophet. Above that, the kalama (profession of faith) is written in large font on a band across the top. This top calligraphic border, and the animal allegory at the base of the picture, could be viewed as mutually reinforcing.

This poster was probably created specifically to publicise Premier Ziaís institution of sharia as the law of the land, although I unfortunately have no other information as to the poster's distribution and use. Thus, I read the cosmic animals, lion and goat, standing together in the pond--unlike their deployment by Emperor Shah Jahanís artists--to here signify the peace and justice wrought not by a human ruler but by Allah as conveyed to his Prophet and embodied in the Quran and sharia. How this Jesuitic-origin-Shah Jahani allegorical animals figure survived into the mid-20th century, in poster art, is a question for further study.

It seems fair to comment on the harsh discrepancy of feeling as between the Shah Jahani picture with its cosmic animals and the Pakistani poster. The depiction of the Mughal emperor appears benign, it connotes a divinely-inspired, benevolent justice available to his petitioning subjects (however far from reality this message may have been), whereas the Pakistani sharia poster connotes both a theological as well as a legalistic message of obedience and the harsh justice meted for disobedience.

Although representing human and animal figures is condemned in Bukhari and other hadith, and depicting the Quran in association with figural imagery is supposedly banned, in this poster these proscriptions are transgressed. Here, the artist's depiction of the Quran together with sinning humans and cosmic animals sternly presents a legal and moral message. In addition, while the Quran in Sura Saba:13 permits figural painting (presumably of animals or humans) for beautification purposes (the context is King Solomon decorating his palaces), that motive is absent from this poster (which anyway is not based on an esthetic of beauty.) The hadith-ic prohibitions on figuration of animals and humans are also ignored, resulting in a curious ambiguity. In wahhabist ultra-conservative Pakistan under General Zia, where figural depictions might be expected to be strictly avoided, the publisher of this poster would appear to have gotten away with a lot. Perhaps he made it under direct order from the government of Pakistan as a means to propagate the news that from then on the country was under sharia law. It still is today.

*(This article is drawn from a longer one presented at a conference in 2003.)

Bibliography

Beach, Milo Cleveland and Ebba Koch. King Of The World: The Padshahnama. London: Azimuth Editions. Distributed by Thames and Hudson, 1997. Burgel, J. Christoph. The Feather of Simurgh : The "Licit Magic" of the Arts in Medieval Islam (Hagop Kevorkian Series on Near Eastern Art and Civilization). NY: NYU Press, 1988. Centlivres, Pierre and Micheline Centlivres-Demont. Imageries populaires en Islam. Paris: Georg Editeur, 1997.

Kirkpatrick, J. Transports of Delight : The Ricksha Arts of Bangladesh. A CD-ROM. Pakistani poster figure from, "Peaceable Kingdoms, or, The Cosmic Waterhole. A Comparison of Popular Images from the USA, Pakistan, and Thailand," (my article in the CD-ROM, Readings file). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2003. Koch, Ebba. Mughal Art and Imperial Ideology : Collected Essays. London: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Welch, Stuart Cary, ed. Gods, Kings and Tigers : The Art of Kotah. Munich and NY: Prestel-Verlag, 1997. ---------------------------- Joanna Kirkpatrick retired in 1994 as Professor of Anthropology from Bennington College, where she taught for 27 years. Author of The Sociology of an Indian Hospital Ward, articles and reviews, she has conducted fieldwork in South Asia on folk art, gender studies, popular culture, and medical anthropology. Regular contributor of Mukto-Mona

|

|

||

|

|

|

|||